The biggest threat to the shorelines of Maryland’s Assateague State Park aren’t the throngs of tourists or galloping hooves of its wild horses: It’s climate change, the effects of which are eroding the island’s iconic beaches, dunes and diverse habitat.

This summer, the first of two new design studios from the University of Maryland’s architecture program examined how the park can ride the wave of change, rather than fight the tide. Working with Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and UMD’s Partnership for Action Learning in Sustainability (PALS) program, students developed architecture and landscape design plans that adapt to the island’s increasingly dynamic conditions, offering hope of resiliency for Assateague’s visitors, wildlife and fragile ecology. The student’s findings will help inform a redesign of state park facilities and a resiliency plan, currently under way.

“Barrier islands like Assateague are landscapes constantly shifting regardless of climate change,” said Michael Ezban, who co-taught the course with Associate Professor Jana VanderGoot. “Often with resiliency plans, there are two schools of thought: We can try and fix things in place, like putting up a sea wall, but there’s another paradigm, which is to flex and work with the fluctuations. That kind of adaptation is key to what we were trying to do here.”

Located off the southern tip of Maryland’s Eastern Shore and extending south into Virginia, Assateague Island is a 37-mile barrier island on the Atlantic Ocean, home to diverse flora and fauna, including maritime forests, clams and, famously, over 150 wild horses. The island’s untamed beauty makes it one of Maryland’s most popular and profitable state parks. Along with other sections managed by the National Park Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Assateague Island hosts nearly 3 million visitors a year for day trips and camping.

While Assateague has been at the mercy of ocean currents and tidal movements throughout its existence—and indeed, as a barrier island, was created by such forces—a recent escalation in climate-induced sea level rise and intense storm activity has made its future uncertain. Climate change models predict a sea level rise on Assateague of 3.5 to 9 inches by 2040. This, combined with increasingly intense weather patterns, batter the island’s interior by pushing water and sand inward, washing over campgrounds and degrading the island’s ranger facilities and public spaces.

“In essence, you lose your beach and the buffer between the beach and the infrastructure we have in the park starts to shrink,” said park Manager Angela Baldwin, who has worked on Assateague for 22 years. “Our mission is to maintain as many amenities and resources in the park for as long as we can, and we knew from past projects between PALS and the DNR that working with the students would be an opportunity for some great ideas and some great concepts.”

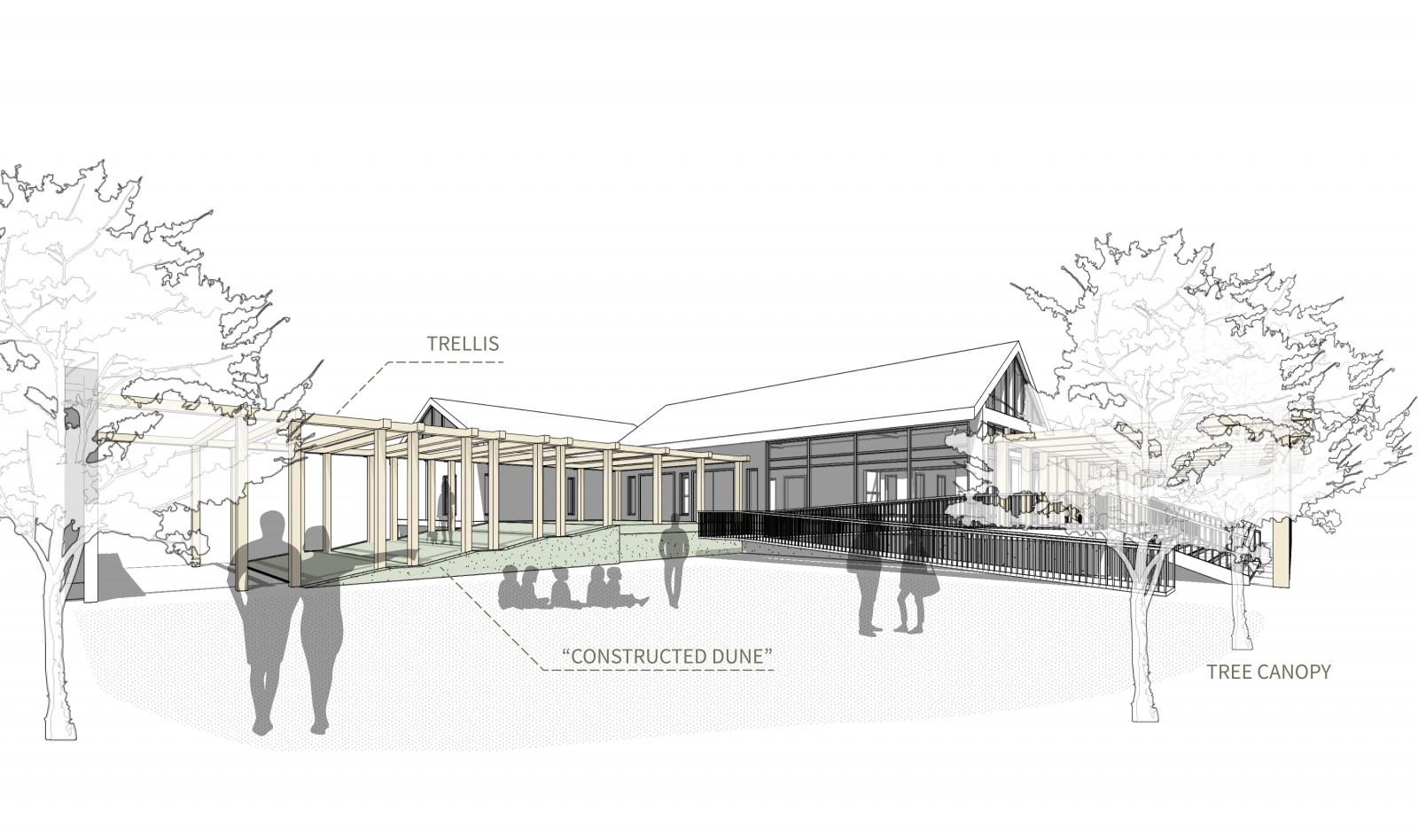

A June site visit and study of the island’s ecology and inhabitants informed a resiliency master plan for the Maryland portion of the island, recommending strategic placement of beach grass, constructed dunes and sand fencing to reduce sand wash and maintain the shoreline. Swapping crushed shells for asphalt in parking areas would help manage storm and seawater while storm-ready photovoltaic canopies and cedarwood trellises would offer shade for parking and pedestrian pathways, the students found.

“Working so closely with the client and taking the time to research the different typology of landscape really helped us create a holistic, more adaptable design concept, and oftentimes we don’t have the time to do that,” said architecture student Yan Konan ’22.

Students reconsidered Assateague’s popular camping loops and how park managers could maintain access to the treasured island for years to come. Students proposed decreasing the number of RV sites, which require fixed infrastructure and paved lots, to carve out more room for tent camping, allowing rangers to shift infrastructure in response to dune conditions and weather events.

“Rather than reduce camping opportunities in the face of eroding dunes and shifting sands that regularly cover the campgrounds, we proposed adapting the campsite layouts with flexible loops and diversification of campsite types at the park,” said Ezban.

Students also designed a new ranger station and its surrounding landscape, elevating and orienting the building to protect from sea spray and weather while capturing southern sun and prevailing winds. Although not part of the proposed project, the students recommended strategies to improve the large asphalt parking lot outside the station. Permeable surfaces, wayfinding and entry points, outdoor and educational spaces transformed the existing acre of asphalt adjacent to the ranger station, connected it with the campgrounds and offered a sense of arrival for visitors.

“They brought some fresh eyes to an area that’s not really attractive or sustainable, and having those concepts gave us some great ideas for components to make the whole area safer, welcoming and more resilient,” said Baldwin. “It was really exciting to see.”

She said the DNR and the project architect are working to incorporate some of the students’ work in project plans currently under way for Assateague State Park, and believe they could be translated to other parks in the region.

This fall, students will focus on another high-traffic area of the island—the Pony Express, a multi-use facility that houses the island’s gift shop, showers and beach facilities. Students from the summer studio will carry the knowledge they learned this summer to the fall studio, along with the understanding that good design should extend past a building’s front door.

“Before this studio, I considered the surrounding landscape of a building to be pretty arbitrary,” said architecture student Nicolas Dibella ’22. “This studio has really opened my eyes to how landscape and architecture can play off each other to create sustainable, resilient design.”