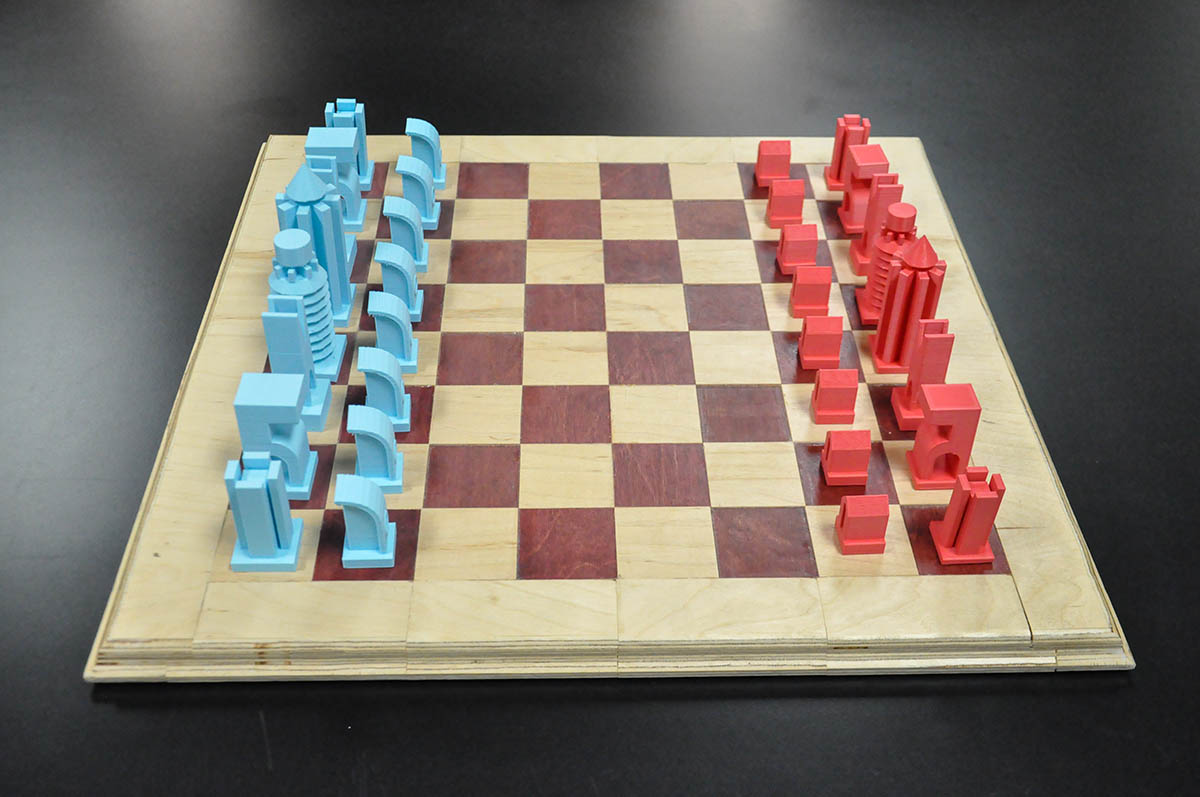

For Maryland’s architecture students, the start of a new semester is a clean slate. The same could be said for the Architecture Building itself: Hallways that are bare in January slowly accumulate grand cathedrals and Victorian-style rowhouses, while modern skyscrapers and city blocks erupt from studio desks. By each May, the school has the makings of a small city, with the emphasis on small.

Modelmaking has been a longstanding method for teaching architecture students how to transfer ideas off the page through the basics of geometry, shape and scale. Beginning their freshman year, students use models to present a finished project but also as a quick-and-dirty method for developing a design concept. Dozens of full or partial models might be built as a project takes shape, with cardboard and filament subbing for glass and steel, while thimble-sized people gaze at the buildings through treetops of cotton.

“It’s a great process tool for testing ideas out,” said architecture graduate student Maisha Islam (‘24), who designed a recreation building concept for Assateague Island last semester with classmates Jihee Lee (‘24) and Samantha Jamero (‘24). “There are a lot of things you begin to notice when you build physical models that you might otherwise miss.”

Models can also show things a drawing cannot: how sunlight filters into a room, the proportions of a building or how people navigate it. Paired with topography or a street grid, models can illustrate how a building can fit into the environment, activate a space or add to a community.

“At the end of the day, most of what we’re designing is physical space,” said architecture Lecturer Alex Donohue. “With a model, you can see all four sides, peer inside it. More importantly, you’ll know if it’s going to stand up or not.”

Over the past decade, laser cutters, 3D printers and cutting-edge software have supplemented the mostly manual process of creating a model’s angular facades, millimeter-sized window frames and intricate moldings. Yet students often return to the old standbys of chipboard, X-Acto knives and glue for their miniature masterpieces, carved and painstakingly assembled over several days.

“There’s something about using your hands through the whole process that’s really enjoyable,” said architecture graduate student Yan Kohan. “And when it’s done, it’s very satisfying.”

There was just one year that the Architecture Building went without its miniature masterpieces: 2020. Students returning this past fall seemed to make up for lost time, said Assistant Clinical Professor Brittany Williams ’07, working at a pace and enthusiasm she hadn’t seen in her 10 years as a teacher or during her time as a student.

“After 18 months of remote learning, they were just starved to make something together,” she said. “We’re using modeling more aggressively now because we’ve realized what a community builder it is.”

At semester’s end, some models stick around: Chipboard facades built by students in the 1990s still adorn a wall outside the building’s studio space, while others hover over the stacks in the Architecture Library.

“I could never throw one out,” said Adrian Mora ’22, who has dedicated a bookshelf to past creations in his college apartment. “Too many hours go into them. To me, they’re little pieces of art.”

Photo courtesy of Jelena Dakovic.