To develop an idea for his final graduate school project 25 years ago, Architecture Clinical Professor Michael Abrams didn’t draw inspiration from his favorite architects: He riffed off his passion for music.

Jazz, with its swinging groove, offbeat rhythm and layering of instruments, influenced his design for a jazz school for teenagers and young adults. The final design offered a whimsical space with melodically inspired elements—from a slanted red wall that symbolized a musical interlude and tension, to suspended classrooms that mimicked musical notes on a staff.

Music is just one art form that can spark inspiration in the sometimes-challenging early stages of a designer’s process, said Abrams, a concept he explores in his new book, “Metaphoric Architecture: Transforming Ideas into 3D Form." Released this month by Routledge, it takes a unique approach to design thinking and breaks down how elements of art, music and film can inspire abstract ideas for creating 3D objects, spaces or buildings.

The book’s four chapters–design fundamentals, art, music and film––help students, instructors and designers understand the importance of metaphoric architecture and highlights how building physical 3D models can offer a more tactile experience for designing for a three-dimensional world, said Abrams. Each chapter contains visuals, case studies, projects, tips and exercises, with examples from Abrams, colleagues and architecture students from the University of Maryland.

“Metaphoric Architecture” takes a different direction than Abrams’ first book, “The Art of City Sketching: A Field Manual,” which focuses on sketching as an aid to capture the built environment. But, in both, he highlights the critical role imagination plays in the design process and what it looks like for architects to dive into a sense of playfulness, exploration, creativity and thinking “outside of the box.”

“Sometimes you find inspiration from areas you didn't even realize you could get inspiration from,” he said.

Below, Abrams demonstrates how a famous painting, a musical instrument and an Alfred Hitchcock's classic film can inform and inspire an architectural design:

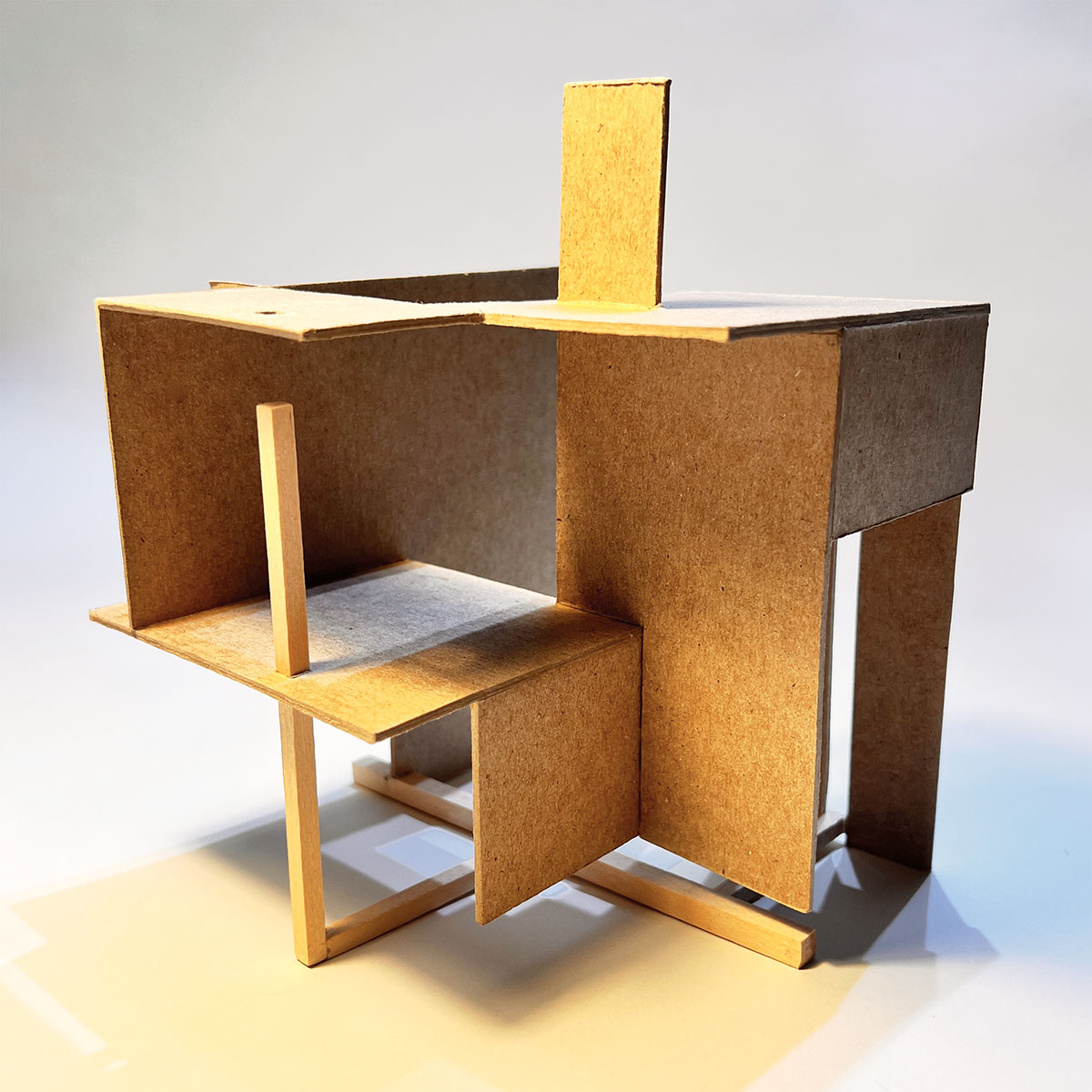

“The Mondrian Object”

A 2025 class assignment at the University of Maryland challenged students in Abrams’ “Design Media and Representation I” course to analyze an abstract painting by Dutch artist, Piet Mondrian. They transformed elements of the artwork, such as its geometric shapes, lines and primary colors, to create a cubic object with wood, glue and chipboard.

The project taught students the importance of transparency and structural integrity in modelmaking, said Abrams, and helped them understand how to create a sense of openness between the interior and exterior for a structure, while also maintaining its form and function.

“As we move from painting to diagrams to objects, the painting is no longer as important anymore because then the object starts to take on a life of its own,” Abrams said.

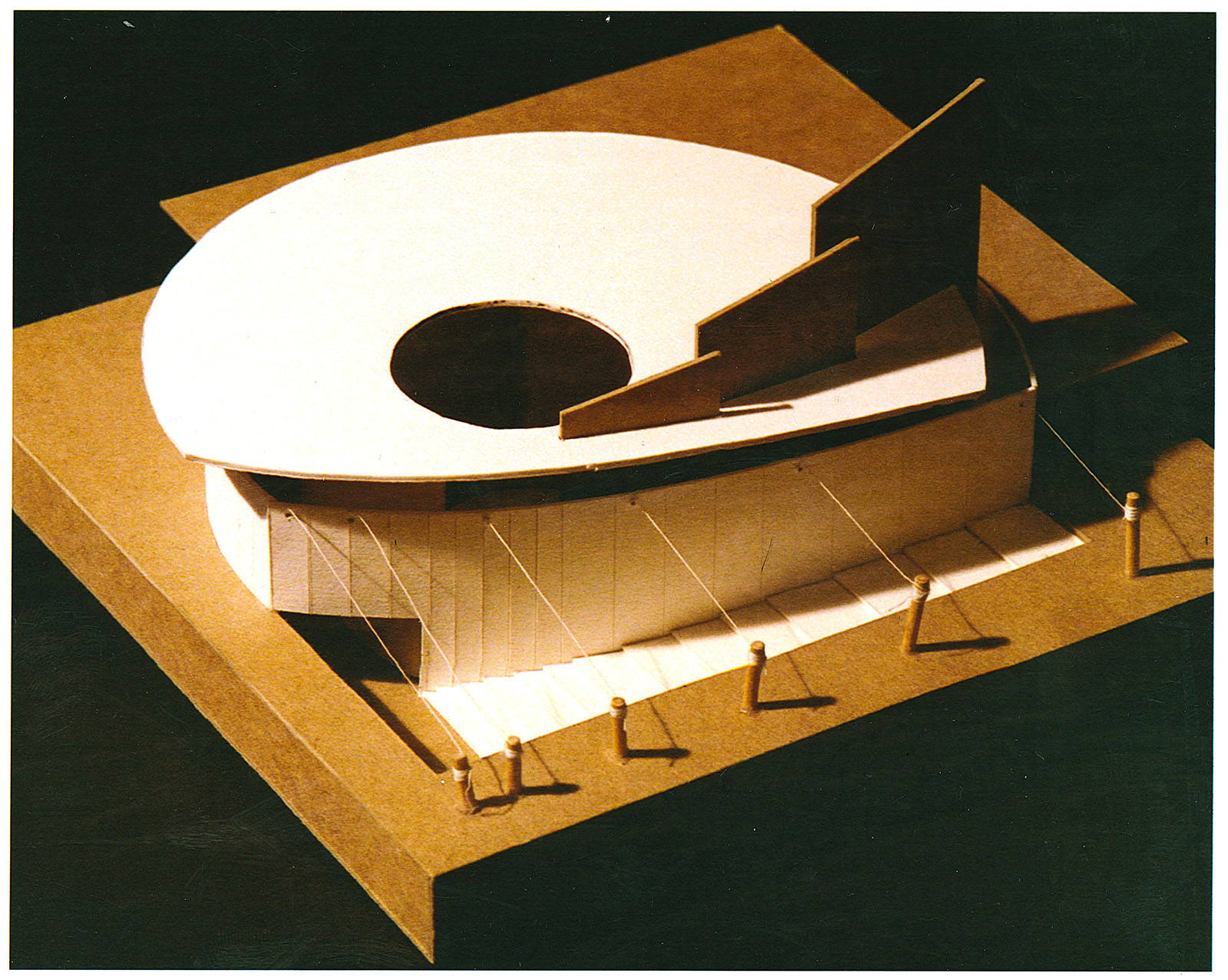

“Guitar Pavilion”

Abrams used the guitar–a hobby of his–as the inspiration for the design of a pavilion, his first class assignment as an undergraduate student. Abrams reinterpreted the fretboard (or neck) as the pavilion stairs, the body as a performance space and the strings as columns attached to the “main load bearing” wall in the building.

“It was the first time that I started thinking about architecture as not just brick and mortar, but as poetry, and as something that is abstract,” Abrams said. “It's a different way of thinking, but then you have to dig [into] that abstraction and make it tactile and palpable to exist in real life.”

“Rear Window”

The view from Jimmy Stewart’s apartment is a character all its own in the 1954 film “Rear Window,” with the courtyard and neighboring building driving the film’s storyline. How director Alfred Hitchcock captured these scenes, said Abrams, is similar to how an architect generates a sequence of movement through spaces: Both consider how people interact with their surroundings. For architects, features like landscape and elevation “drive the plot forward and make the space believable,” he said.